- Foreword

- Homage to Shuzo Takiguchi

Kazuhiko Satani’s Homage to Shuzo Takiguchi

In 1973, at the age of 45, Kazuhiko Satani quit his job at a bank and began working at Minami Gallery, a pioneering force in contemporary art at the time. It was at this time that he began keeping a diary, and he continued almost without missing a day until he fell ill in 2008. His diary entries noted the day’s weather, people he had met and spoken with, and his thoughts, covering both public and private matters.

As an employee of Minami Gallery, Kazuhiko Satani became friendly with Shuzo Takiguchi, a man he had admired for many years. In his diary Kazuhiko unhesitatingly referred to Shuzo Takiguchi with the honorific sensei, putting him in a small group of Kazuhiko’s respected elders along with Hisashi Nakayama (art enthusiast and valued advisor whom he got to know during his days at Minami Gallery) and Ekizo Fujibayashi (Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Japan). In July 1981, two years after Takiguchi’s death, Kazuhiko launched a series of exhibitions in Homage to Shuzo Takiguchi, which became a lifelong project. The Exhibition in Homage to Shuzo Takiguchi was held 28 times, up until 2006.

A Gift from a Poet: Homage to Shuzo Takiguchi

July marks the second anniversary of the poet, art critic, and writer Shuzo Takiguchi’s death. He died at the age of 76. When did I first become aware of Takiguchi? Thinking back on it now, it was 26 years ago when I read his book 16 Profiles: From Bonnard to Arp (Hakuyosha, 1955). At the time, I was a greenhorn bank employee and a humble art enthusiast, who was subscribing to art magazines like Mizue.

After some ups and downs, I gradually developed a preference for contemporary art, and in the process, I learned a great deal from Takiguchi’s books. Along with Modern Art, Discourse on a Fantasy Painter, Ernst, Fontana, Points, Writing in the Margins, To and From Rrose Selavy, and A Painter’s Silent Parts, there were out-of-print titles that had been published before the war, such as Dalí and Miró, which I searched for at used book shops in Tokyo’s Jinbocho district. I was particularly surprised to find that Miró was the first collection of criticism on the artist to be published in the world. Although today it would not be in the least surprising, given that Miró is a widely known and great painter, the fact that a book on Miró was written in a Far Eastern island nation prior to the war in 1940 is highly significant. The only word for it is “far-sighted.” At the same time, I would like to emphasize how clear and easy-to-understand Takiguchi’s criticism and commentaries on contemporary art were. In general, contemporary art commentaries were difficult, and that being the case, they took on a stronger glow the further you moved away from them.

Takiguchi also made (and supervised) numerous outstanding contemporary art translations. These included Herbert Reed’s The Meaning of Art, Azansha’s Dictionary of Modern Painting, and Marcel Brion’s Abstract Art as well as landmark works such as André Breton’s Surrealism and Painting (Koseisha, 1930). This was the first full-fledged introduction to surrealist painting (a movement that emerged in Europe following World War I) to be published in Japan, but perhaps more importantly, it was the work that determined the direction Takiguchi, who was 27 at the time, would take in the future.

It was this André Breton, the leader of Surrealism, who Takiguchi met in Paris in 1958. In his autobiographical chronology, Takiguchi described this as the “harvest of my life.” I saw a picture of the meeting in Mizue. A Far Eastern poet of small stature was shown talking with Breton in his study surrounded by countless art objects. To me, the photograph gave me the feeling that I had seen Takiguchi. It made a distinct impression.

In 1968, a major solo show by Sam Francis, one of the preeminent American Abstract Expressionist painters, was organized by Minami Gallery and held in the Hankyu Department Store building in Ginza, Tokyo. Around that time, my interest in contemporary art had grown even stronger. I had bought some prints by artists like Francis, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jean Fautrier at Minami Gallery, and I had changed to the point where I even attended a launch party for the exhibition, though I was seated far from the guest of honor. On this occasion, I saw a gray-haired old man speaking with Francis. Someone told me that the man was Takiguchi. I thought to myself, That old man is Shuzo Takiguchi, and I sat there looking on with rapt attention as if I was watching a scene from a movie at some distance. Fans are essentially people who silently stare from a ways away. Takiguchi had many fans of this kind, and I was one of them.

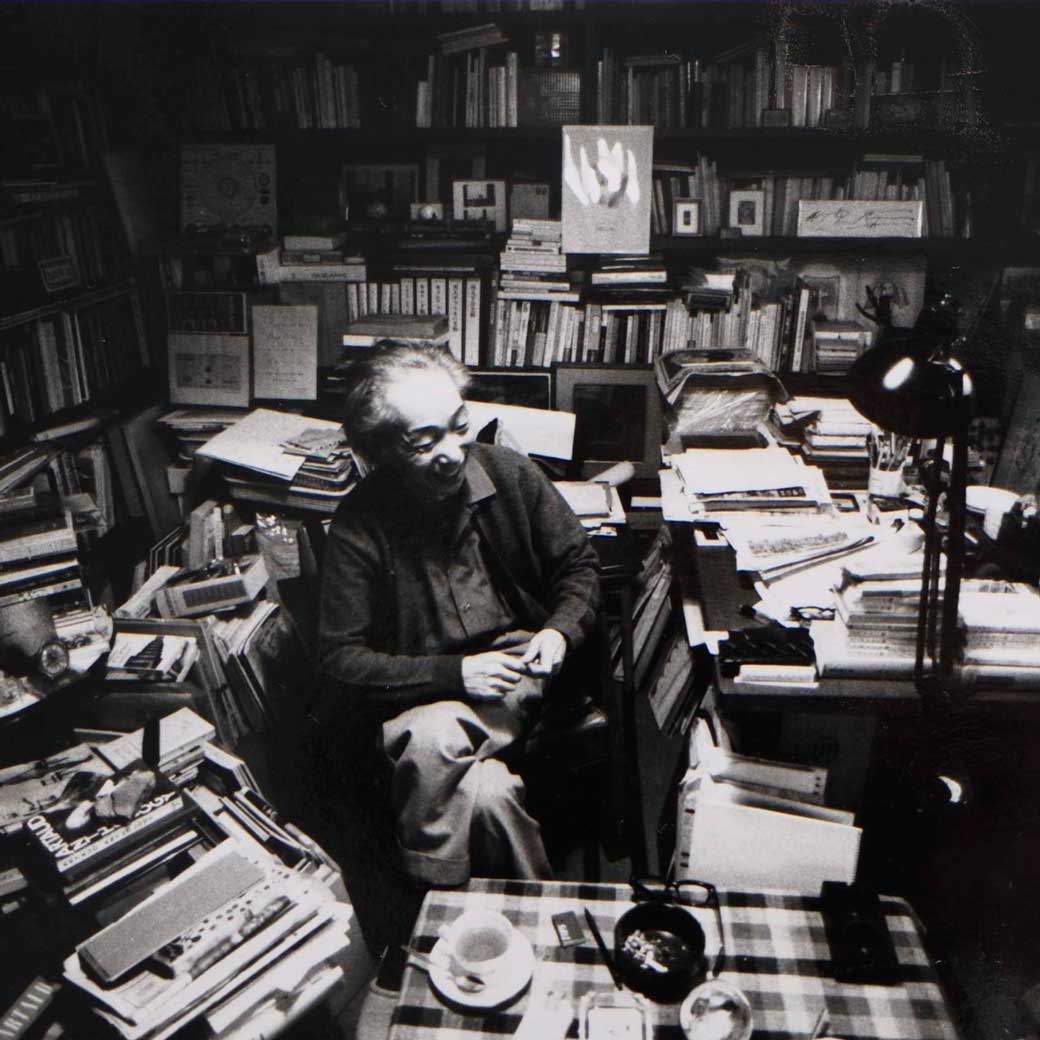

Shuzo Takiguchi. Photo by Mitutoshi Hanaga

In 1973, after eagerly receiving an invitation to work at Minami Gallery from the gallery’s director Kusuo Minami, I boldly quit my job at the bank, where I had worked for 20 years or so, and went to work at the gallery. That was a major historical event for me. To commemorate the event, I decided to publish a small booklet titled After Picasso. This was a collection of about ten essays on contemporary art that I had published in the bank’s in-house magazine.

I gave the booklet to my company seniors, friends, and Takiguchi. I wavered over the content, which seemed immature and embarrassing, but the book owed a great deal to Takiguchi’s writings, and I secretly wanted to convey the fact that I had set out off on this new course.

Not long after, I received a courteous letter from Takiguchi. The beautiful writing was in blue ink, and my heart beat wildly, as if I had just received my first love letter:

“Your mention of me in the text made me feel embarrassed, as if I had met someone in an unexpected place. Today, after zealously attempting many trials and errors over many years, I remain dumbfounded at myself, as someone who has acquired nothing and still continues to search in the dark for the wrong things. I imagine that many difficulties lie ahead for you in your work, and in Japan in particular this field remains virgin soil (despite being quite rugged), but I am confident that in as much as there is a great deal to be cultivated, it will be a worthwhile pursuit.”

Even today, I reread this letter, dated July 24, 1973.

After coming to work at Minami Gallery, I sometimes had a chance to meet and talk with Takiguchi. He was still in good health at the time, so I occasionally listened to him talk over a beer at a small eatery or food stand in Ginza. As his healthy declined, my heart ached when I saw him slowly walking as he supported his small body with a cane.

His house was in Ochiai (Tokyo) and I would occasionally visit him there too. There was a big olive street in the garden of the shabby wooden one-story house. I met [the poet] Tatsuji Miyoshi in his later years; he was a lodger. The idea of a poet living in a gorgeous mansion seemed out of place, but even so this seemed overly frugal. As I saw it, life was simpler if you turned away from the world, strictly regulated yourself, and placed the freedom of the spirit above all else. This is how it seemed to me when I saw the attitudes of these two poets.

But when I entered Takiguchi’s study (cum drawing room), it was a different world. The eight (?) tatami-mat room was completely packed with books, published collections of paintings, paintings, sculptures, art objects, posters, and more. Takiguchi quietly sat in a small, shabby chair without a back. Around the table and chairs where we sat, there was an ocean-like surge of books, magazines, catalogues, letters, documents, and other things. The proof for this was if I mistakenly put down a book I had brought with me, it wouldn’t take long for it to disappear, seemingly sinking into the sea. You might say the study was a magical space – or a galaxy – that was truly Takiguchi’s world. I heard many stories from him there about Breton, Dalí, Miró, Sam Francis, Jasper Johns, Joseph Cornell, Henri Michaux, Antoni Tàpies, Lucio Fontana, Duchamp, Ernst, Hans Bellmer, Man Ray…. There were all kinds of fragments like this scattered around Takiguchi, so he never had any end of things to say. It was customary for me to end our conversations, as I was worried about the state of his heart.

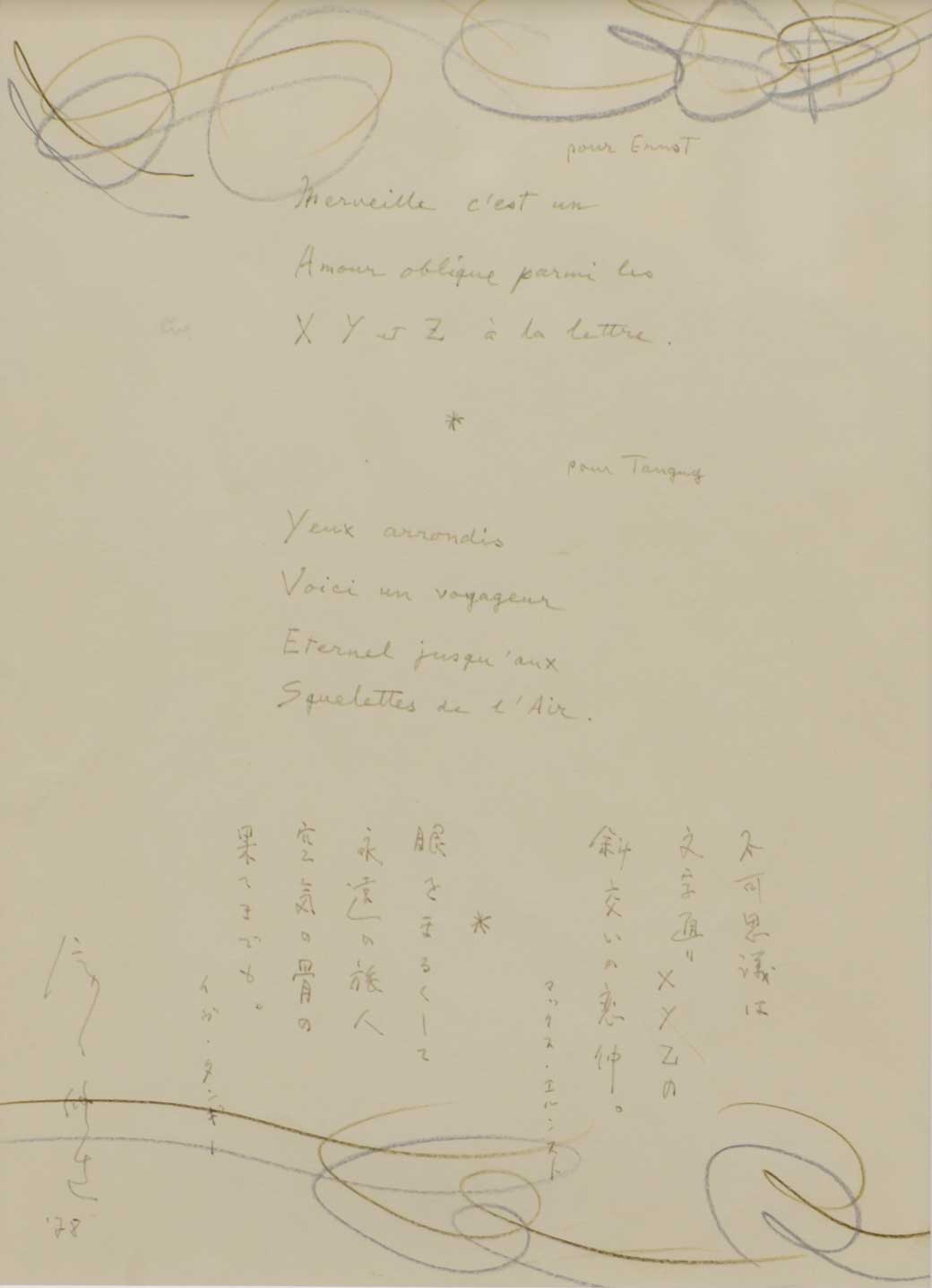

In March 1978, I opened my own gallery. In September of that year, I held the first special exhibition, a two-man show of prints by Ernst and Tanguy. I sent Takiguchi the exhibition catalogue and a few days later, I received a large yellow, special-delivery envelope from him. I wondered what it could be, and when I opened the envelope I found a poem titled, “Pour ERNST pour TANGUY,” accompanying a letter to commemorate my first exhibition (see photograph). The poem was an anagram made up of the letters of Ernst’s first name, “MAX,” and Tanguy’s first name, “YVES.” It was written in pen, and there were gold and silver lines written with a fountain pen at the top and bottom of the paper. This unexpected gift filled me with immense joy.

At the same time, I received another splendid present from Takiguchi: a warm-hearted human communication. This communication is eternal. Today, I am once again sending out Shuzo Takiguchi’s signal.

Kazuhiko Satani. (An essay from exhibition catalogue Material Glancea, 1981, ca. no.016)

Shuzo Takiguchi, pour ERNST pour TANGUY, 1978